The following is a transcript of Zigzag-en-abyme: Michael Moshe Dahan and Juli Carson in Conversation. It was recorded on Monday, August 9, 2021 in tandem with the exhibition: The Messiah Triangle.

Introduction

In this chapter of Life Worth Living, entitled The Messiah Triangle, we publish a transcript of Zigzag-en-abîme: Michael Moshe Dahan and Juli Carson in Conversation. The conversation took place on August 9, 2021 and addressed Dahan’s newest film project, Yes Repeat No, Act 1. The film’s broad subject addresses Judaism, Christianity, Islam: three religions whose messianic impulses have resulted in history’s greatest and most violent conflicts as both religious and nationalist wars. The Messiah Triangle, as an exhibition at UC Irvine’s University Art Galleries, interrogates these conflicts through the refractive, diamond-like prism of one individual born at the intersection of Israel and Palestine: actor-activist Juliano Mer-Khamis. Drawing on Mer-Khamis’s films, media interviews and public persona, The Messiah Triangle is comprised of a conceptual film, Yes Repeat No, Act 1, and a series of large-scale lenticular stereoscopic diptychs, Life Drive / Death Drive, to pose questions about the inter-generational legacies of trauma and national identity.

Juli Carson: I’d like to begin by discussing a psychoanalytic phenomenon that my colleague Mary Kelly has derived—a “political primal scene.” It’s related to the pre-Oedipal primal scene—both of which are Freudian—to talk about foundational trauma. The Oedipal primal scene has to do with sexuality and identity and is completely unconscious. The political primal scene is subsequent to that on a conscious level. I’d like to augment Kelly’s notion of a political primal scene as occurring not once, but twice, the first in early adolescence, the second in early adulthood. But if these scenes are conscious, we should say they are more closely aligned with what Freud called a screen memory. Accordingly, each stage of the primal scene (and both together) align with a given historical event, which, in turn, contributes to the formation of a political identity. That said, this political identity is at first very problematic. Hermeneutically, I think about adult art production as a third point—a self-critical, theoretical view of the world—as subtending the first two more naive political primal scenes. And so what I want to talk to you about are the two “political” scenes followed by that third moment of critical reflection by way of art making.

Michael Moshe Dahan: I actually had to call my mother about this today, because I couldn’t tell if this memory was actually from my childhood, or my adolescence, or a story I’d been told about my childhood. It had to do with being evacuated or forbidden from going into a an outdoor restaurant in Tel Aviv because an explosive had been found. I had to call my mom and say, “Did this happen, or have I constructed this event from all the things that I think happened?” Because it really was hard for me to remember. There are times when one remembers something from their childhood and subsequently realizes “that’s just a photo that I looked at repeatedly in my adolescence of my childhood, and I’ve retroactively projected a narrative onto it.”

I had thought that this was a memory from when we were living in Israel, which meant the first seven years of my life. My mother reminded me that it wasn’t actually from that period of time; it was actually on the first return visit after we had left to live in the States. So we left in 1979. I was seven and a half years old and then we returned at some point in the early 80s when I was about 11 or 12. Which meant that that memory actually was from my adolescence; originally I thought it was much earlier—when I was five or six. The experience of coming back to Israel as a 12 year-old was quite jarring for me because I’d spent so much time and effort as a seven year old erasing any cultural differences to fit into the kind of North Carolina milieu that my parents had dropped us in for a couple of years. From Jerusalem to Raleigh, North Carolina. I made every effort to repress anything I could—the Hebrew language disappeared when I tried to learn English as quickly as possible. When I returned to Israel that first trip, I was really a stranger in a strange land in Israel, and I was really out of place here in America. Meaning, I had not yet assimilated completely into one culture, even though I’d worked so hard to get disconnected from another. I had blond kids with freckles asking to see where my tail was when I was standing at the bus-stop in Raleigh, North Carolina. I returned to Israel to see my extended family— which was huge with 10 uncles and aunts on each side—each with their own children. Emotionally, all that family felt to me like home. But I also felt very much out of place—I wanted that feeling of home but did not fit into my family anymore. This “bomb at a restaurant” memory accompanies all of that return back to Israel, along with some acculturated understanding that bombs are a regular part of life, being told repeatedly that “Arabs are a kind of menace associated with bombs.” Moreover, not even understanding really at that point in my life as a 12 year-old anything significant about the history of Israel at all, except these very clear emotional valences that had been imposed upon me by my family about what was bad or good.

That’s all you learn when you grow up and that’s all I had learned at that point, or at least that’s what I remember having learned which was, you know, there was a kind of fear of public places. There was a fear of airplanes, and there was a fear of buses and restaurants. That is the extent of what I actually understood cognitively. That event, it turns out, did occur but it just wasn’t when I was 7. I thought it was in my childhood, but it happened when I was 12. I can’t tell if that’s a constructed memory because it just signifies so much about what I understood at the time of the event, and at the time of the construction of my memory.

JC: It’s interesting because, as Freud says, there are two kinds of memories, both of which are as fictional as they are factual. Right? The first constitutes screen memories, wherein an early event is recalled and transformed into memory by a contemporary event. The combination produces for the recalling subject an event that never in fact happened. But the so-called “authentic memory” of an event—one that can be validated from a third person perspective—may not be completely accurately recalled (how could it be), but it’s not a screen memory because the event actually happened. So when you called your mother, it seems you were asking, “Is this a faulty real memory, or is it just a screen memory?”, it seems like she was basically saying, “No, that’s a screen memory.” Because memories of childhood are always retroactive—one period is recalled over the other—which, you know, brings you back to your adulthood. Which, in turn, brings us to the more recent moment when you decided to do an MFA, constituting your art making adulthood. Prior to that, there was your filmmaker adulthood—you were a film executive, then a commercial photographer and photo retoucher—and after the MFA you went on to study for your PhD. So you’ve got this robust history of so-called adulthoods, but there’s a thread that goes through all of them. Do you want to talk more about that?

MMD: I spent a decade or so in the film industry working for a number of producers—the last of which was Mark Gordon—his thing was doing historical dramas, historical epics. He was known for films like Saving Private Ryan, and The Patriot (for which I received my first credit as an associate producer) and Grey’s Anatomy. What I did with him were historical films—before I left his company, I started to develop a movie about the crash of 1929—which became a topic that you and I later collaborated on curatorially. There was then, and still now, a real sense of history and historical knowledge, myth-making through narratives (of the American Revolution, of WWII) tied up for me in filmmaking. Saving Private Ryan had such clear, black and white values—you know: Nazis bad, Americans good—it was a very Manichaean setup for a film. With Mark, I really felt like I learned from somebody who had a serious regard for certain things that had to do with history—because that’s where so many of our film projects came from at this company. Ultimately the film production process was unsatisfying because I was working on $200 million films but really as a story project manager—a development executive—not nearly creative enough.

I decided to go back to school at that point to be a commercial film director, and then I went back into photography, and then I did some work in commercial photography photographing celebrities, musicians and doing a lot of photo retouching. The MFA grew out of a complete dissatisfaction with commercial work in which the outcome was far more important than the process. All commercial work is oriented more towards the outcome for the audience and how do you give them what they want. Those concerns to me were less interesting—it was much more interesting to me when I started working, or at least having a dialogue with artists, about what that process actually was. This is what led me into the MFA and that was 2012— 12 years after I’d left the film business. After I’d spent time as a commercial photographer, composing one single frame at a time, I evolved into entering an MFA program, looking for a challenge—a way that I could stay engaged beyond outcome.

The kind of things I was engaged in before the MFA, for me, were problematic. I was also retouching a lot of stuff for advertising so I was learning how to manipulate photos. But again, I was taking cellulite off of a celebrity’s ass, or something like, that for an ad campaign. It didn’t feel like something I should be doing forever. But I think each of these pursuits accumulated into a set of skills that, initially, I didn’t have a sense that I could put together.

JC: So when you get into UC Irvine’s MFA program you have all these extraneous skill sets. Working with you at the time, it seemed like there was dissatisfaction with how they were previously used and a hunger to use them towards something else. And beyond all this practical stuff, there was this lurking—soon to be— screen memory. So, as they say in film, all the elements were there: you have a crisis that’s repressed, a robust set of undirected skills, and a creative-epistemological drive. As I recall, it was all going on in the first year of your MFA, a lot of stuff just bubbling up.

MMD: I didn’t have the discourse of art, I didn’t understand what people were saying or how they were talking about it. I learned soon after that most of what people were saying was garbage, it was bullshit, but the point is I felt intimidated by a language that wasn’t mine. And so, for the most part in my first year in the MFA I kept to myself and worked on the things that I thought were interesting but felt a very distinct pressure both internally and externally. People were challenging me about the kind of art that I thought I was making based on all these technical skills that I had—but this set of disparate skills were still in need of a discursive subject. And again, this is something that goes around in the hallways of MFA. Your identity and your history really become this thing that people start to mine for themselves like, “If I’m Middle Eastern, I am obligated to make work about that particular political situation.” Similarly, in PhD programs, your personal identity lends credibility to your research project.

What I soon realized is that I knew so very little about my own upbringing. I knew that there was something to be mined but it was closed off to me at that point. It was like a tomb that had been sealed that I was trying to stumble through while making work. The only thing I could muster in that first year was something I’d remembered from my childhood about walking home from school to my nanny’s apartment in Jerusalem and not understanding which ‘side of the street’ I was supposed to be on to get to her house. My mother had told me, “Cross the street here and then her apartment building is just around the bend,” and I thought I had crossed too early and so I crossed again, and then crossed back, and crossed again. I ended up crossing five or six times, in a walk from the bus stop that was maybe 50 meters. I was, after crossing so many times feeling so completely disoriented and lost that I didn’t know where I was any longer. I tried to follow the directions, and I followed them almost too well.

So the photo installation, Aporia, was the first work that had any relationship to my past, and I thought it was about walking to my nanny’s house but really it was about not understanding which ‘side of the street’ I belonged, both literally and metaphorically.

JC: I remember that because we worked together studying a lot of psychoanalysis at the time. But I also believe I was teaching my Hannah Arendt seminar at the time, which had Eichmann in Jerusalem on the syllabus, you know, her infamous critique of the Israeli trial. I recall that you were extremely interested in this material, but hadn’t really spoken about your Israeli background and about how conservative your upbringing was. Your parents actually moved to Israel in December of 1967 just before the Six Day War. Which is interesting because Juliano, your subject in Yes Repeat No, Act 1 had a zionist mother who changes her position 180 degrees, but your family never did. And I remember thinking, like, ‘good lord,’ when that did come out, you know, the schism between what you were doing in seminar, with the critique of Israel, and what you would have to go home to daily with your father. But you were very mindful of the split, and I think that something, of this current project originated in the very first year of your being at UCI.

MMD: When my parents arrived in Israel as North African sefardim, they were not treated very well themselves—and felt like outsiders in Israel. I didn’t even know my family was conservative politically—because in Israel even open-minded, progressive citizens have somewhat conservative views when it comes to Israel’s existence—despite any costs, and all of the implications about land seizure that follow from that. I didn’t even have a sense of what that meant until I started reading Arendt with you. I went to visit them in Israel that year, over a holiday, sometime at the end of the year. I remember trying to even introduce my mother to Arendt. My parents are smart people. My mother is very well read, but just introducing the name Hannah Arendt, you know, at Shabbat dinner—I almost got into a fistfight with my father because I didn’t even know Arendt would be so offensive to them—there was simply no room for nuance in their historical understanding, their myth-making. It was a complete shutdown for my father. Things like this were not necessarily discussed often. Remember that my parents chose to leave Israel because they didn’t want their children to serve in the military, because they wanted better opportunities for themselves—so on some level there was an understanding on their part that politically the situation wasn’t stable, but the nuances of that weren’t necessarily communicated to us. The myth was what we got.

JC: This is why the metaphor of crossing the street is a very powerful metaphor for your family life and Jewish holidays in Israel, Middle East, and America.

MMD: Emotional indoctrination is so under the surface that you don’t understand it. It’s something that attaches people to the concept of a nation, but I don’t think I understood how much of that was part of my upbringing.

JC: To borrow from Louis Althusser, that’s what ideology is, it’s like Roland Barthes’ notion of myth…something completely unconscious while it’s working on and through you. You only see it when you’re no longer a subject of it. Yours is an interesting journey, but it did not happen overnight. It happened very organically for years and over many projects. At the same time, you generated many other projects that returned to the earlier “work” things you did; you just mentioned that you had worked on a commercial feature film on 1929. That had to be formative for your take on the “Libidinal Economies” UCI exhibition and MUMOK film series that you and I collaborated on. So a lot of these things constitute a process of what Freud called “working through.” A sort of analysis that’s not like going into actual psychoanalysis, but it’s nevertheless a self-aware, self-reflective process of working through childhood and young adult “things,” through writing theory, making art, and discussing these ideas with people in your PhD program. All this has brought you to where you are now. Even so, it took you even longer to land upon a project from which this film springs forth.

MMD: I started the MFA in 2012 we’re now 2021. I felt very strongly that I wanted to examine, understand and interrogate my relationship to Palestine. I knew that I wanted to understand my relationship through art production and theory and that something compelling would come out of it. I didn’t feel like I could even speak a sentence until I actually understood the nuances and complexities—which my upbringing did not expose me to. In 2015, I entered the PhD program and started to do research, broadly, trying to understand the kind of critical issues in the region through my work with you, David Theo Goldberg, Mark Le Vine, Julie Burelle and Bryan Reynolds. The political, historical understanding of the Holocaust and all of the kinds of discourses that emerged from that interest. I didn’t feel that I could make artwork until I had a sense of that complexity and nuance. I didn’t realize it would take me almost 10 years to get to a point from the start of the MFA where I felt prepared to return to art production.

My inquiry in the PhD built upon the MFA. I’ve sought to think through art production that’s been generated after, and out of, unspeakably unrepresentable traumas like the Nakba and the Holocaust, many generations after the fact. These traumatic events are not fully worked-through by the first or second generations that experience them. Rather, they get worked through decades after by generations who may have had the same kind of encounter with historical trauma that I have: through the whispers, or elisions in retellings of family histories. These traumas that happened are known about but sometimes only spoken in whispers and never discussed openly until you’re being indoctrinated by a history that is colored by political influence, which is not particular to Israel. I left Israel in the first grade, way too early to absorb all of the indoctrination. The narratives around the Holocaust, and the establishment of Israel, to me were foreign right until I started to think through art production and what happens with traumas that are repressed or not worked-through—how they somehow get distorted in these subsequent generations. That’s where my inquiry began—with artists, who were working in a similar vein through film and video, let’s say, about this kind of trauma. Subsequently interest started to really get focused around the time we did the ‘When is Beirut’ symposium (November, 2019), which was happening concurrently with the film series exhibition Beirut Lab: 1975(2020) that you curated for Room Gallery at UCI.

JC: Yes, that show was a filmic adaptation of a show I produced with my students at the American University of Beirut, entitled caesura__a moment in time, again rubbed smooth, while I was doing a year-long residency in Lebanon. When I returned to UCI and adapted that show into Beirut Lab, I’d asked you to co-organize and moderate a panel as part of the show’s program, which we titled When is Beirut?

MMD: For me it was a really interesting way of understanding all these issues I’d been working around. I started thinking about how to apply some of your lines of inquiry from Beirut Lab and what that would look like if it was attending to works emerging from Palestine and Israel by these artists who really were second and third generation from the Nakba, generations that were still dealing with it. I found so much interesting work. But after two years of trying to put artists together for a thematic exhibition, we could not make it work. There were artists from Palestine who had real objections to even being housed in the same space as Israeli artists who— even though they were very progressive politically and were making work that was very critical of the Israeli nationalist project—didn’t want to be in the same exhibition. Understandably, they didn’t want to be tokenized, they didn’t want to come to represent a point of view that was being almost ventriloquized by Israeli artists.

JC: Let’s back up. So basically after Beirut Lab, your dissertation became focused on these issues of trauma triangulating between Beirut and Jordan (or the Palestinian diaspora) and Israel. And that actually aligns with when I was coming back into the Directorship of the UAG Gallery, having taken a sabbatical from that for a couple of years. I suggested that perhaps you might use the model I did, when I got my dissertation at MIT, which was to do research at the same time as doing an exhibition about the same subject matter. And that’s how this Messiah Triangle show came to be. And that’s when you found that the subject of triangulation—which we should now talk about—was so traumatic that you couldn’t get people to comply. No one wanted to be in the show with anyone else. At which point, I remember saying, “This dilemma is the project. Perhaps you have to make a film.” I remember Professor Stefania Pandolfo (UC Berkeley) had concurred. So you heard this from two people at the same time.

MMD: The nature of the exhibition, as it was becoming focused, really had to do with the way in which the kind of Messianic impulses in Christianity, Islam and Judaism had these parallels, all of which had led to the kind of impossibility of the current political climate. What I was finding again and again was that I couldn’t solve this problem by curating an exhibition because I had these incredible artists who had a forceful resistance to being curated into a show with even the most politically conscious and progressive Israeli artists. They presented a legitimate argument that has also been made by scholars like Ronit Lentin that even the Israeli left—and, by extension, artists of the Israeli left—are often, primarily, or simultaneously attending more to the reparation of their own egos than actually trying to help Palestinians change their conditions. It’s a critique about “allyship,” a so-called alliance that, with all the best intentions, ultimately doesn’t do enough to change real conditions on the ground or have real political consequence.

JC: Which is when I said that’s the subject; you’re the subject. Write a film about it.

MMD: Yes, and I thought, “Oh God, this is an impossible task—I have to now make a film about this impossibility.” I remember calling Stefania Pandolfo—who was a brilliant contributor to the When is Beirut? Symposium—after your suggestion and sharing our conversation. She also suggested that I try to solve this conundrum of the impossible curatorial project as an artist. It was not in my head at all—it’s such a different set of skills; curating and art production. It was very hard for me to switch gears, especially because we’re talking about April of this year when we were having these conversations in particular. One of the other things that Stefania said to me-—it was almost like like the punctum of our conversation, so I just couldn’t let it go—she said “You know you’ve got to be careful because there’s another person who tried to straddle the line of impossibility between this one political moment and this narrative, historically—meaning Palestine and Israel or even the triangulation between Christianity, Islam and Judaism—and that’s Juliano Mer-Khamis.” I’d heard the name, I’d heard about the Freedom Theater through Professors Bryan Reynolds and Mark Le Vine, with whom I was working at UCI.

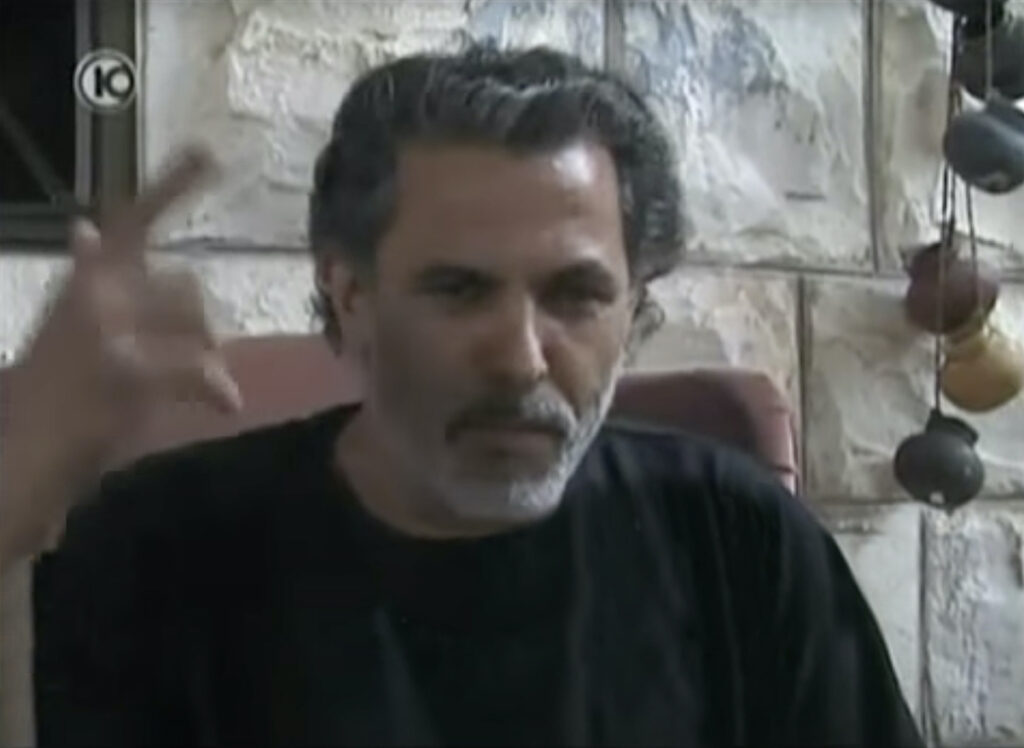

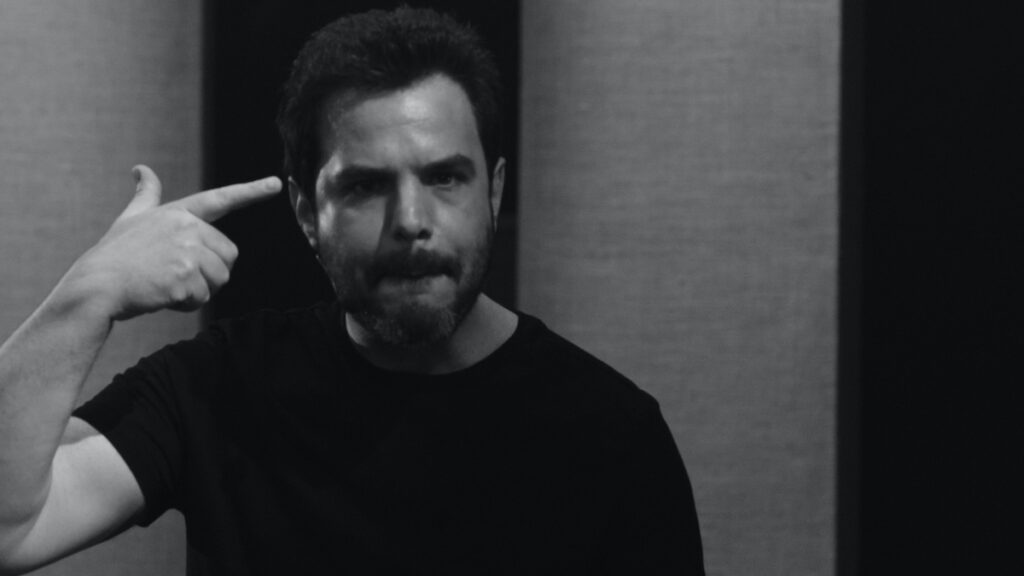

When I got off the phone with Professor Pandolfo, I went into a research hole for a few days because I wanted to understand exactly what she may have meant: Why was he in the same situation—or what, if any, were the similarities she might be suggesting. The first thing that I understood about him—which I thought was very compelling to me—was that he was an activist in the sense of how you might conventionally think of an activist. He was doing work on the front lines of a conflict. He had a theatre company that was exposing the youth of Jenin to a politically radical approach to performing plays, like Alice in Wonderland, and infusing some of these political undertones into them. In 2011, he was assassinated for that, and perhaps for what he himself represented: His father was Christian Palestinian and his mother was Jewish Israeli. He was the very intersection of those two identities. He spent time in the military as a paratrooper earlier in his life, trying to hold on to his Israeli identity and then kind of revolt against it later on in life, when he became an activist. So there was something about who he was and who I wasn’t that was compelling to me at first. I thought, “Well look at him with his long hair in Jenin doing the good work of political activism, and look at me sitting in a hermetically sealed room, reading a lot about activism.” My reality wasn’t about being an activist but about thinking a lot. So I was feeling almost impotent in terms of art production because I couldn’t get these artists to work together, and then I had to turn on this other part of my brain related to art production that had been turned off for the last eight years during my PhD research.

It was a crisis for me because I didn’t feel like I was up to it. Nor did I know what it meant to be an activist, because I wasn’t that guy with long hair in Jenin fighting it out with the IDF and living with these freedom fighters. Juliano faced this impossibility and died for his cause—whatever that means in the romantic sense of things. I’ll admit that really struck a chord.

I subsequently watched these videos where he speaks of his own death. How does a person have a premonition of their own death and describe it, and do so repeatedly and give it almost as a soliloquy, a monologue that he’s given many times before? There’s a video of Juliano Mer-Khamis where he says, “This is how I’m going to die… some fucked-up Palestinian is going to shoot me in the head for bringing this blonde wife and corrupting the youth of Islam,” putting himself in a kind of Socratic position. And I thought there was something really interesting about that and—

JC: —it’s Messianic, the way that he’s speaking about his own death.

MMD: Yes, but not only simply in that statement, but in the way he is spoken of and spoken about, and the eulogies and memorials in elite progressive circles of New York intelligentsia. All of this activism and his persona had a narrative that traveled well—the story traveled well. I’m not saying the activism wasn’t legitimate to some extent but there’s just something about the currency of being that person which had a messianic flavor because it represented how you’re “supposed to do” activism.

JC: Basically, what’s interesting about the exhibition you were trying to curate is that you couldn’t get anybody to comply who literally was alive. Moreover, you were thinking about people who were lumped into three demographics—you know Christian, Muslim and Jewish—in terms of this overarching Messianic proposition that has a lot of tangible geopolitical implications. Not directly, in a direct colonial way, but more on the level—to evoke the punctum again—of a Lacanian real, which is to say, the objet-a of the Messianic drive. Accordingly, there’s this enormous amount of jouissance around your subject, which is not something people like to talk about. Because it’s often problematically expressed as, “Well that’s the Middle East, where there’s all this jouissance; just let it be.” Which is not your point at all. But there’s this the dumb version of what you’re trying to do, lurking out there, which was something your curatorial project couldn’t escape. What I came to understand only later, once you discovered Juliano, was that a set of conflicting demographics and regions was embodied within this one fraught person. Consequently, his project did not survive—he did not survive. Analogously this conflict was embodied by the collective of artists who declined to participate in the your show. From this perspective, I see your project as a kind of film stand-in, a synecdoche perhaps of the failure of art production, on the one hand, and the assassination of a person who embodied a perspective that dare not speak its name.

MMD: Right.

JC: So let’s turn to your artwork now, The Messiah Triangle. From the start, you chose not to biographize Mer-Khamis. Instead, you chose to do two things at once, zigzagging, again, along the road. This is a metaphor that strings through our conversation—a zigzagging between making an art project and an experimental time-based installation, using film. Not to forget the festival-bound feature-length film that will eventually be produced from all this. But the thing that all these genres share—the artwork, the time-based installation, the experimental film—is that they’re neither fictional nor documentary. Moreover, in no phase of this project do you take a narrative approach. Rather, I would say that your project, writ large, returns to a kind of Brechtian rehearsal modality. Hence the title Yes Repeat No. Let’s begin with the title before we unpack what you were doing with the actors and everything else. How did you come up with the name Yes Repeat No?

MMD: I started researching all of the films that Juliano Mer-Khamis made as an actor; after he spent his young adulthood in the IDF doing the military service, he decided to become an actor. At first he became quite a well known actor of theater and film in Israel and then started to branch out in the United States. His first feature was one made by George Roy Hill in 1983, based on a John LeCarre novel, The Little Drummer Girl. In that film Juliano plays a Mossad agent—a background player with only seven lines in the entire film—who’s part of a group of Mossad agents trying to recruit an American actress named Charlie, played by Diane Keaton. A cable comes through for the Mossad from their superiors, as they’re interrogating Charlie, but, importantly, after they’ve already revealed they are Israelis. The field office in Jerusalem cables them to say that “Under no circumstance, should you tell Charlie that you’re Israeli– just say that you are Americans.” Klaus Kinski brilliantly portrays the commanding Mossad agent. It’s absurd to him because they’ve already started the script to recruit Charlie, and they’ve already revealed their nationality. So his response to his field office is “yes repeat no” which is a military term is used in the Navy, as a, as a confirmation that you received an order, but that you don’t agree with it, and are not planning on following that order. So it’s, “Yes I’ve heard you, repeat, no, I’m not going to abide.”

The phrase is so conflicted within itself. It’s also a concise and impactful way of keying into this process of contradiction. Immediately, I knew that would be the title of anything I was going to make about this. In a synecdochic way, that small part of Juliano—that role in The Little Drummer Girl—really begins to stand in for so much more. There’s something about the fact that Juliano seems to be in conflict with himself— especially when he was younger and says “I was looking for who I was.” He first attached himself to his Israeli identity, and it was horrifying to his mother that he joined the IDF because by that point she had rejected her commitment to Zionism. He spent a couple of years as a paratrooper, and is cited and detained for some kind of insubordination when he doesn’t want to harass one of his own Palestinian relatives at a checkpoint. This attachment to one identity comes full circle and crashes in on itself. After he decides this is not the identity he wants to attach himself to, he becomes an actor and starts to become an activist by helping his mother build The Stone Theatre. His mother passes away and he doesn’t return to the Stone Theatre in Jenin for a few years, but then returns to make a documentary about her, Arna’s Children, in which he discusses these conflicts in his life: He first rejects his Palestinian side by joining the IDF, and then he rejects the Israeli side by becoming an activist. What’s so interesting is that he’s doubted by everybody. He’s doubted by Israelis for potentially being a collaborator and he’s doubted by Palestinians who think, “Well why would this person help us? He must be a spy.”

Meanwhile, there’s no proof that he was and there’s no proof that he wasn’t a spy. But if you look at the facts, he did spend months with resistance fighters, and that’s what’s so interesting about his documentary film Arna’s Children. A lot of these kids he worked with start off as seven year-olds who want to be actors because of the work that Juliano exposes them to in The Stone Theatre and subsequently the Freedom Theatre. That’s what they aspire to, but they eventually become freedom fighters and a number of them either die or end up in jail. And that, for him, was a kind of shocking realization.

JC: The inevitability of their outcome.

MMD: And then, of course, the fact that he himself gets killed in 2011 by religious conservatives who probably felt like he was violating the very fiber of everything they believed in. But make no mistake, he could have just as easily been killed by religious conservatives and extremists in Israel as he could have by the Muslim conservatives in Jenin.

JC: Like Yitzhak Rabin. So now, yet again, we have another story, a stand-in or synecdoche, not just for the region but for you, in an interesting way, as you arrive at a different problem. How do you make a film about that?

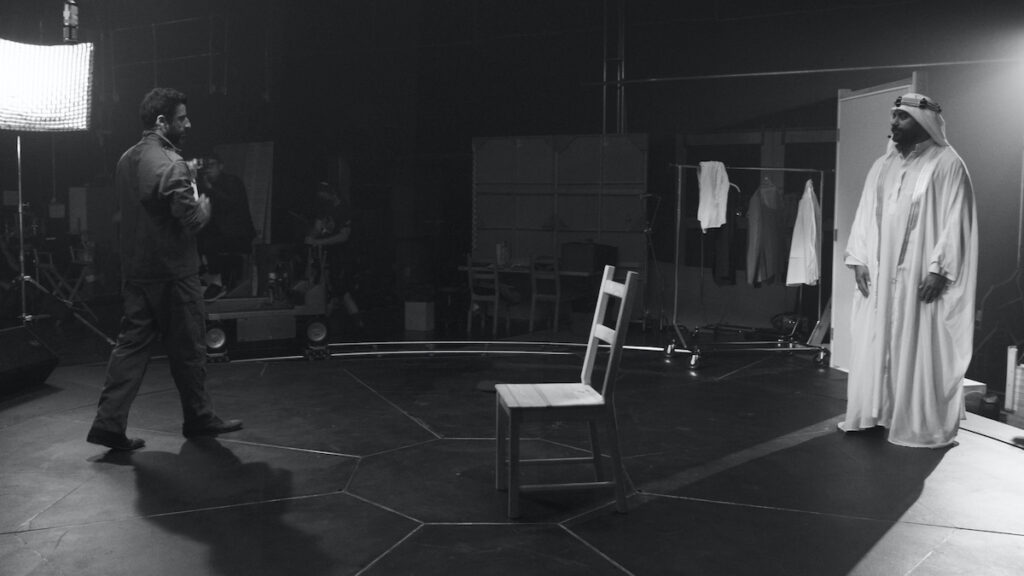

MMD: This is the way that these things happen for me. So many years of research amount to a kind of a lucky find, or Lacanian tuché. Like a flash, something occurs. And the idea that came to me emerged from these different parts of Juliano. And maybe, those could be portrayed through different actors who all want to be Juliano—I really was thinking about a competition. Who would be the “most” Juliano? Would it be the Israeli facet? Would it be the Palestinian facet? The Israeli version is the actor, that’s what he was when he was in Israel. He was an actor. That was his first incarnation, and then there came the activism which is Juliano being a director. That to me is the Palestinian side of him. Actually, two of my actors—Mousa Kraish and Karim Saleh—came up with that general formulation. And then there’s the public persona who—in his matured state, in his mid 40s—realizes that it’s not that he’s one or the other, but that he actually occupies a place where he can shuttle between these two things. He can always leave Jenin and go to Tel Aviv for the weekend if that’s what he wants, something few of his students in Jenin could do. He can always go to New York to raise some money if he needs to. He can and does occupy all of these positions. So there are three actors, they each want to be Juliano, one of them is Israeli one of them is Palestinian. One of them is the kind of public figure that understands that he mediates both of these positions—he’s neither one nor the other. That is a thing that I see as very common to both Israelis and Palestinians, or Christians and Jews, or Jews and Muslims. There’s a kind of attachment to your narrative, your origin myth, your identity that precedes all other discourse or conversation that you’re going to engage in.

You have to be one or the other and you can’t occupy both, you can’t be in between them—that’s too dangerous a position. People really want you to have a position to argue from, so they can argue against it. And I think that I was interested in how to trouble these attachments to the one or the other, to the binary. This setup, which was that there are three actors, they all think they’re Juliano, and what happens? They audition to be Juliano, and then they get mad at each other because they each individually thought they were the Juliano; they get push back at the director, but they can’t get out of this situation, unless they achieve something. The closest kind of parallel to that was No Exit—that three characters find themselves in a situation in which they don’t have control over when they can and can’t leave—and their entire existence in that purgatory room is defined by how they are not like the other, l’autre. That was my first initial thought.

I started the process by choosing not to think through the entire narrative beyond that initial formulation. Rather, I considered what happens when you put three characters together—they’re all coming in for an audition; they each come in to audition for a separate little piece of this Juliano but on the pretense—at least in their minds—that there is only one Juliano role. That’s the first act that will premiere as an art installation at UCI. In the subsequent two acts, they’re introduced into the same environment together and they’re not allowed to leave until they solve a certain problem. This has traces both of No Exit, Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, and even the logical problem of the three prisoners and the Warden that Lacan sets up in his “Logical Time and the Assertion of Anticipated Certainty: A New Sophism.” The problem was not really important. The problem was another narrative device that I would deploy. It’s the fact that they’re confined and they come from different political, personal, cultural affiliations that become stand-ins for these bigger issues, and that they can’t leave. They don’t have a say of when they can. That’s really how it started. When I sat down to write it, a flood of research, production and thinking and theory were merged together, and distilled into the script—which took maybe 48-72 hours to write from start to finish (not including revisions which continued into production.)

JC: It’s a script that you wrote that’s based on occupying another script, which is to say, the plot of The Little Drummer Girl.

MMD: The Little Drummer Girl became really important; first that it was Juliano’s first major film role, but also that it’s a story about recruiting somebody to the “other side.” Diane Keaton plays an activist named Charlie (based on a real person that LeCarre met named Janet Lee Stevens) who’s also an actor, which I thought was fascinating to me in that you have this guy Juliano who ends up a decade or so after this film becoming an activist after being an actor. There’s something about the way that Charlie is recruited in that recruitment scene. You have to understand as an Israeli kid who moved to the United States, the Mossad—the Secret Service in Israel— was this mythical object you were always taught to be proud of, to find appealing. Again, that’s the seven year old me who has this romantic attachment to what the Mossad means, what it symbolizes and the pride I’d been taught and did feel about Israel—the synecdochic function of the Mossad in relation to Israel. That I had any understanding of Israel—its history or politics—or none at all, didn’t really matter. What I knew was the Mossad was badass. That’s what I had been taught…

JC:…highly highly mythological, the Mossad. I’m thinking of all those recruitment myths. One, I don’t know whether it’s true or not, is that you have 15 minutes to go into an apartment and get the owner to give you their keys, which you demonstrate by standing on the balcony, or something like that…

MMD: …It’s a baseball cap. You have to come out wearing a baseball cap that belongs to the owner of the apartment. It was documented in a book called By Way of Deception—which of course I read when I was in college along with many other spy novels. This book is all about the Mossad, and it’s really fascinating because you hear all those legendary anecdotes about what you have to do to prove that you are worthy of being a Mossad agent. I loved spy films. I grew up in the 80s watching spy films that made you feel like being a spy was a cool thing to do. Flash forward, and now I’m looking at this film from the 1980s about the a Mossad recruitment scene. Diane Keaton is a sympathizer for Palestine, she’s an actress. She hates Israel because she knows you’re supposed to be critical of Israel, she might not even know completely what that’s about—but she says all the right things.

JC: They don’t know what that side’s about, they only know that it’s the right side.

MMD: They call her out about this in the recruitment scene when they confront her by asking, “Well, what have you done really, you’ve read Che Guevara in Trafalgar Square, but really what have you done?” They goad her: “What are you prepared to do?” It’s very clever—you’ve done nothing, but if you really want to do something, you should do this. They finally recruit her into going undercover into a Palestinian training camp, in Lebanon. They convince her that by doing this, she’s actually helping the Mossad take control of a situation that would otherwise be controlled by madmen on both sides, both the side of the West, meaning Israel and the United States, or the side of Palestine, where it has been presumed or mythologized that there are people who are irrationally making decisions. And only the Mossad can help. Just as only the CIA in the 50’s, 60’s 70’s and 1980’s has the moral authority to meddle in everybody’s business because we know what’s best.

It’s a developmental approach to international relations where America is the parent that knows best for everybody so let us meddle with our money and our spies. The recruitment scene became the crux of that film, but it also became the crux of the geopolitical situation where America meddles through its clients in the Middle East—with money, spies, military and the Mossad—in other people’s business. Now it’s 2021 and we’re looking back at what that really means—that mythological and aspirational world-building status that America gave itself the post-WWII period. And we see in the trash heap of post-Trump, what that really means—not only has Trump shat upon the possibility of that world-building concept, he made us look even worse in our overall decision making, constantly. The veil has been lifted and not even a supposed “return to normalcy” can remedy that. I thought it might be compelling in 2021 to be looking back at 1983, particularly at this scene where you’ve got the German-Jewish Israeli Mossad commander Marty Kurtz, the Israeli-Arab Joseph (who in the book is not Israeli-Arab, just Israeli). George Roy Hill, in his film, really invents the character in all its nuance by casting a Greek actor, as a more ethnically ambiguous figure: Is he Arab-Israeli or is he just Israeli that looks like someone of Arab descent against Diane Keaton who plays the silly American actress?

In the full film Yes Repeat No, that scene becomes crucial because the three actors are being asked to solve a problem, and the question is: what is the problem? Well, the problem is which of the Julianos—Israeli, Palestinian, or the Public Persona—should play which role: that of the Israeli Marty Kurtz (the Mossad commander), the American activist (Diane Keaton), or the Arab-Israeli (Joseph, who’s also posing as a terrorist named Salim but goes by the pseudonym Michel). The only way to solve this for me was through process. They each should alternately play (Israeli Juliano, Palestinian Juliano, Public Juliano) and each inhabit the roles (Jewish Kurtz, Arab Israeli Joseph, American Charlie) for some time in the piece. Meaning they should rotate, circulating around those roles, because I’m interested in troubling the attachment to an identity that’s fixed in order to generate a friction between those fixed positions. And the only way to create that frottage was to have the actors substitute in for each of those roles at different times. From there, the piece wrote itself. Knowing that the actors show up to audition, work out a given scene, and that that scene has to be played three times, once by each. There’s not much room left for anything else, meaning that’s your narrative. Once that situation is conceived, once the bones of the structure are in place, the characters really began to speak themselves and the story tells itself. They have to take certain positions because otherwise there’s no drama, no agonistic struggle. In that way, it was actually quite easy to write—it was much harder to come to the decision to write.

JC: I think it’s a good time to acknowledge we’ve thus far, in this conversation, definitively buried the lead. Because there’s another film, one based on another real live event, that precipitated your entire project denoted by the phrase The Messiah Triangle, the film component of which is Yes Repeat No, Act 1. So buried in here is yet another facet of the project’s “origin” story. I think you should talk about that.

MMD: We talked about this three years ago I think when we were sitting together, face to face at lunch, and you were saying “I think that you should think about this…” We were talking specifically about When is Beirut?, but also about the structure of my dissertation. I carry these components all the time, wondering about their configuration together, creatively—a theory, an aesthetic, a historical proposition—following the critical aesthetics model you’ve developed. There was a book that I was told about maybe twenty years ago, which I finally got around to reading six or seven years ago. An old partner of mine in the film business said “Oh this is a book I really want to make into a film—don’t you dare tell anybody about it.” And I said “Ok I won’t tell anyone about it but, I might use it for an art project.”

JC: [Laughing] “Yeah, I promise I won’t tell anybody about it (while I’m making a film about it).”

MMD: I didn’t tell anybody about it—I just read it and thought it was a fascinating case study. The book is called The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. It was actually made into a Hollywood film—it wasn’t made by me and it wasn’t made by this ex girlfriend of mine—it was made by Richard Gere. The book that it was based upon was written by a social scientist named Milton Rokeach in 1964 following his case study from a now decommissioned psychiatric hospital in Ypsilanti, Michigan (now a Honda factory by the way). He had three patients in the same hospital system, not even in the same hospital, who all believed they were Jesus Christ, all with delusions that they were the Son of God. He decided to treat them by putting them into group therapy in the same ward. Rokeach believed that if he put them all in the same room, they would inevitably understand their delusion and would come to their “rational” faculties. There’s an even earlier case study that Foucault cites, about Simon Morin, another patient in the 17th century who has a similar condition of believing he had been “incorporated with Jesus Christ,” and who’s put into a mad-house “with another fool who called himself God the father.” Morin concludes he must not be Jesus Christ if this other patient, who is really crazy, believes he’s God. In The Three Christs, Rokeach constructs an encounter between three patients who all think they are the Christian Messiah in order to cure them. It doesn’t happen. Meaning, their delusions do not abate. In that sense it’s a failure and ethically questionable. In the coda of the book, Rokeach comes to the realization that he himself was playing God, thinking he could determine how they were going to see their own self image once he put them in the same room together. He really takes himself to task for being so blind to his own God playing. And I thought that was really fascinating—that additional level beyond the three Christs—of the doctor overseer (what for me ends up being the director), who believes himself similarly to be a god.

The Messiah Triangle presents an analogous triangulated mise-en-scène, but instead of three Christs, there’s three Julianos who wrestle with the buried Messianic impulses of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, big ideological players on the geopolitical field. This all comes together quite abstractly and tangentially, each element dovetailing and colliding simultaneously. So when the exhibition version of The Messiah Triangle fell apart, I was thinking about this book that I hadn’t read in decades. It came together both very slowly, and very quickly at the same time.

JC: Towards the end of the project, when the filming began, a monkey wrench was thrown into this perfect little package of the synecdoches for the region—messiah, activist, actor—in relationship to your role as the film director. Simply the script was pure man’s world. In it there were three Julianos and a male director as another character. And then, aha! The realization that the director character should be a woman.

MMD: I thank you for that suggestion. I thought it was kind of brilliant. Initially, I saw the director in the film as a stand-in for me—as a character like Rokeach the social scientist playing God, or even the Warden in Lacan’s three prisoner—because I’m the director and I’m bringing these people in. We made the decision to try to cast three actors in the roles of the three Julianos that kind of looked alike—enough alike that they could be interchangeable, but also human beings that were interesting and could be put into the roles. The decision to cast a woman was fantastic because otherwise it would have been four Julianos and I think the director needed to be something else. I didn’t understand that until we started having the conversation, and then it became almost impossible to not think of it as a female character.

JC: We should talk about production for a little bit. How have the interactions mattered to drive, for lack of a better word, the plot? Retrospectively you can see how different it would have been were the director a man. So what has this female actor brought to the script/stage as the “unknown” variable, which is what women generally bring to a man’s world, the unknown variable. How did this actor/character change the interactions among the other actor/characters

MMD: On a kind of purely logistical level in casting these actors, I was always interested in who they were as human beings. From the start, that was important because this wasn’t purely narrative, nor was it purely documentary. It was important to know that in the encounter between human and role there were going to be things about these people as humans that would matter to the piece. That was another blurring of those clear distinct boundaries that was really important. The first actor that we cast in the role of the director was Israeli. It was important to me that we had an Israeli in the cast, that we had somebody who could represent the Israeli position from a position of sincere commitment and passion, and not from a purely critical position. I wanted to have an Israeli in one of the Juliano’s since his mother was a Zionist in the beginning, as was as Israeli and Jewish. As it turned out, we ended up casting one actor who’s Lebanese whose family I think originally was from Syria, but again it’s not the director. Then one of the three Julianos was Moroccan– and from the same town my mother was born and raised in, Casablanca, and one who is Palestinian.

The female director ended up being an Israeli. She was just the best Israeli actor we could find. I was looking for Israeli actors for that role, and I thought we found somebody pretty good. It changed the kind of authority that she had on set, meaning the kind of authority that she brought to the part. It was no longer a male authority but rather a phallic authority that wasn’t attached to her gender, which created a different level of interaction for each of the Julianos. Each of them tried different ways of encountering her as a person—flirtation, comity, antagonism—and I don’t think that would have happened with a fourth male actor.

JC: Hmmm. So maybe say more about the three male actor’s interactions with you, the real-life male director.

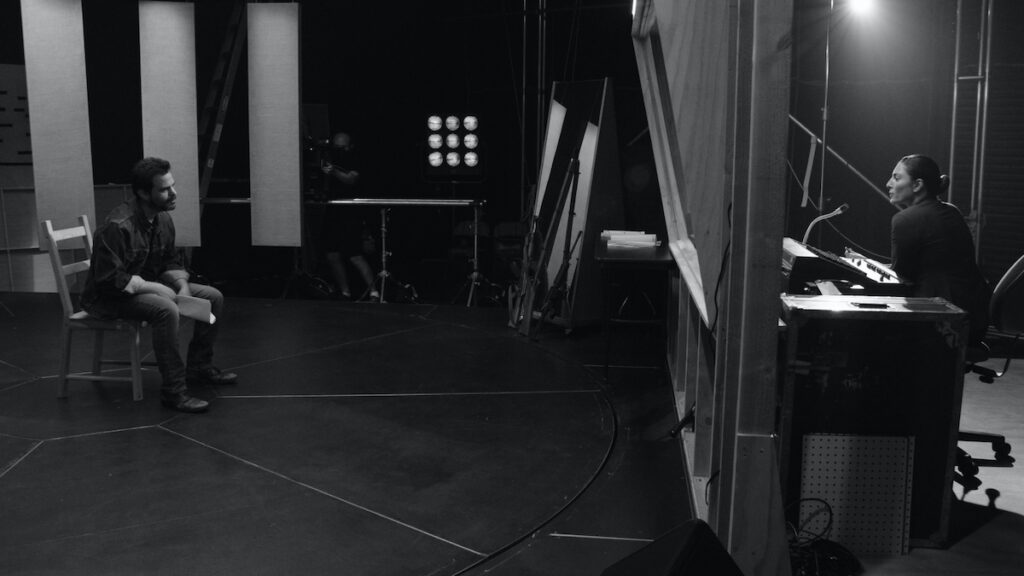

MMD: Well, for instance, the pre-production process included things like a fitting, for wardrobe and hair and makeup, and a separate day for a table read. When I cast the three men, I said, “ You have the part. You’re going to be Juliano,” and they’d say, “Well which part do I have? And I said “I haven’t decided yet.” I wanted us to read the script three times. I wanted to hear what they had to say about each of the three Juliano parts they each inhabited during that table read, and I wanted to see how they encountered each of the parts in rotation.

JC: So actually, in your real-life audition for The Messiah Triangle, you are—unbeknownst to the male actors—rehearsing the actual script.

MMD: It’s the only way to have done it really, because, how would I know if the Palestinian actor should play the Palestinian Juliano, or if the Lebanese actor should play the Palestinian Juliano or if the Moroccan actor should play the Israeli Juliano. I had no way of really knowing—castings are so short, you get about 1-3 minutes to hear someone read. I knew that they kind of looked alike—they had beards and were men—and that they had some relationship to the region. This means that they had some skin in the game, meaning they understood something about it. They weren’t three American actors at a table read who just wanted to play an interesting part.

At the end of the table read, the question arose “Does a Palestinian actor play the Palestinian Juliano or does he play the Israeli?” My producers and I had an extended discussion about what each decision might mean. But a more important event interrupted that process. Our Israeli actor, the female director, started to have objections to how she would personally be represented in the film—because there was a documentary element to the piece. In her mind, if she was just asked to play the part as written—as an Israeli director who was somewhat critical of Israel, that was something she was prepared to encounter. But what she had some resistance to—which ultimately meant that she couldn’t continue in the part—was that there would be parts in between our takes of written dialogue that would also be filmed. To capture this, I instructed the camera department to shoot everything; if we start arguing, as human beings—not as the actors in their role—to continue filming. Because we’re dealing with matters that people can take issue with, everything in the film is something someone could contest: “Well they’re not freedom fighters, they’re terrorists!” I anticipated that those would be rich areas in the film, so I told my brilliant DP, BJ Iwen, “When I say ‘cut’ to the actors and we start talking about the script, you don’t stop shooting. I want you to do six hour takes if that’s what we’re shooting every day.”

She wasn’t the only actor that expressed this hesitation, and fear of retaliation, because there are so many crazies in the world especially around this particular issue. She said, “You know I just don’t know what I’m going to say when we’re having these conversations, and I’m afraid of how that’s going to represent me as a person. I didn’t sign on for this.”

JC: They signed on to be actors in a film—experimental or not—and you then added reality TV to the equation.

MDD: It was kind of thrown back at me in this way—but of course you know reality TV is a bunch of producers whispering in your ear saying, “Do you know what he just said about your mother. Are you going to take that?”

JC: In Reality TV, for every 11 hours of shooting, you hope to get a good five minutes of “action.” And of course it’s the editor/director who get’s to decide (the God issue again). The point is, the actors have even less control of their persona on the set than they do in a scripted film.

MDD: True, but the actor is not out of control either. I was very specific with all the actors I said, “Listen, if we interview you in between takes or we have conversations and you don’t feel comfortable, you can walk away. You can not answer, you can make up an answer. You can make up a fake story about yourself because whatever that is, it’s still going to reveal something about who you are. I don’t care if you want to lie to us and concoct a personality.” For this Israeli actor, that wasn’t good enough. And so, it came down to an ultimatum to change the conceit of the piece for the Israeli actor and their misgivings. And by the way, to remind you the same exact thing happened when we were trying to put together the original curatorial project.

JC: The problem of the exhibition returned. It was repressed, and then it returned in this film production.

MDD: The original challenge with the curatorial project came from a Palestinian curator—who was part of the diaspora—that we were working with who was helping with reaching out to certain artists on the Palestinian side. That Palestinian curator made a similar request, with the curatorial project, as this Israeli actor made with the film. The curator asked why I couldn’t just mount an exhibition with only these kinds of artists, only Palestinians. “Why do you have to include Israelis?” But that was not the conceit of the curatorial project—it could not be compromised. The exhibition, like the film, was to be about the impossibility of the situation. It’s not about taking a side that’s too easy to take: Israel-Bad / Palestine Good—that’s the trendy position. Nobody else needs to make another show about that—it’s been done already.

JC: Though, it will continue to be done.

MDD: But that’s not what we were doing. I had to abandon the curatorial project because I didn’t have the support of an interlocutor who was helping us access a lot of Palestinian artists. So that exhibition went into the dustbin of history, “piling wreckage upon wreckage.” Now I’ve got an Israeli telling me I can say these words you’ve put in the director’s mouth, but I refuse to say anything as myself. So I said you can’t be in the film. And this is three days before we begin filming.

So now we’re out a director, but we luckily had some really strong alternates because of our incredible casting director Emily Schweber. We had someone, Salome Azizi, that could have easily been cast over the first director. Salome was British, but originally from Iran, her family had left during the revolution and moved to London. She had her own fraught relationship with institutional religion and the political outcomes it engenders. Now we’ve got, you know, a Lebanese actor, a Moroccan actor, a Palestinian actor on the Juliano side and British Iranian on the director side. She ended up being a better choice in the end. What was problematic now was that we didn’t have any Israelis in the cast.

We shoot for the first two days. And on the third day, one of our actors doesn’t show up. Previous to this unfortunate absence, I was having some issues with this actor, so I started talking to an Israeli actor that had come in for the part during auditions—as a kind of backup alternate. I didn’t want to be caught without options if we had to replace anyone during production. What I liked about him, Adam Meir, is that he was Israeli, he was in the IDF, he was in the intelligence service for a short time after the IDF. And he was a really good actor and he had a very strong point of view about Israel which wasn’t completely pro-Israel or against Israel. He had spent enough time in the IDF to have some very specific opinions about the way that Israel is represented. He believes Israel’s problem in the world is primarily a PR problem more than anything.

I happen to believe that it’s more than a PR problem, but I liked that he didn’t mind having an argument about his position. He wasn’t afraid of the argument, he was secure enough in his understanding of himself and his history that he welcomed it. Initially, we were actually going to write him into the script as another character (“The Consultant”) because at the very least I needed an Israeli on set, otherwise it’s just too one sided—it’s not fair if we don’t have somebody who is there to represent the Israeli level of commitment. Part of the pre-production process was that I had a script that was already written, I went over it with each actor, and I rewrote specific lines-by-line to make it a more natural fit for each human actor encountering their respective role. There was a lot of latitude for me because there were only a few non-negotiable in terms of what I wanted actors to say specifically as written. Everything else was open for discussion. I also knew that a lot of the material that was coming from this as a finished product would be improvisational, people would bring things to it. A lot of people brought very personal stories that have been woven into the fabric of the dialogue that we would never have had if these characters or actors didn’t have some personal attachment.

So now he had our Julianos. There was Karim Saleh, a Lebanese actor, most likely Christian by birth or had been brought up in that way, though he was not religious himself, as I’ve surmised. He had some historical relationship to Syria, but was somewhat unwilling to reveal too much of that background. There was Mousa Kraish, a Palestinian actor, whose family left because of the Nakba and was raised in Brooklyn. His grandparents lived in Deir Yassin and were expelled in 1948. And there was Adam Meir, an Israeli. All of a sudden, who these actors were as people became really important to the piece.

JC: But now they’re being directed by this phallic female, who’s Iranian British.

MDD: An Iranian-British female who, being very honest and straight-forward, said “I don’t know if I know as much as everybody else about this, I hesitate to speak too much because I don’t know if I have the authority to speak.” And I thought her honesty about her positionality was wonderful. That’s how I felt when I started this whole process a decade ago. “The only thing that you owe us,” I said to her, “is your honesty.” It’s ok to come from the position of “I don’t know if I have any authority to say this, but I’m wondering if you guys can explain this to me.” This is what we want on film. A number of times in pre-production the actors would want to engage about a certain topic and I’d ask them to save that for rehearsal—I didn’t want to overcook the piece before we got on camera. I wanted to work it out on camera.

JC: As of recording this conversation, you’re not yet in post-production, but you’ve successfully ended production. Now you’ve got the artwork on the immediate horizon, and the completion of the feature film just beyond that. So you’re simultaneously running this film marathon and this exhibition sprint…with the film on the far horizon and the exhibition on the near one. What then are your aspirations—upon completion of production, going into post production—of this as a critical project? As a cultural critique of the phenomena that you’re addressing? I think going into the project you’ve had a very strong conceptual North Star. But since its inception there’s been a lot of variables and contingencies that’ve made the project more fascinating, more intellectually robust. Coming out of it, why was this worth doing or how was it worth doing differently than you’d envisioned? Where are you going now?

MMD: We have 250 hours of footage. That’s what I’m starting with. In my mind, this is a body of work from which many concrete pieces will fly off. The nature of the process was really about process. There were times when actors would start doing things in the scene like “ I don’t know what page we’re on,” and I’d say “Come on man, We’re on page 12,” and the actor would look up at me and say “ I’m acting, you idiot. I know what page we’re on, it’s the character that doesn’t know.” There were all these moments where we couldn’t tell if they were acting—are they about to get into a real fist-fight or not? And I think because of that, the process of the narrative—the process of the experiment—become material in the experiment. What can it be from here? There are almost too many things. I’m not trying to complete the complete film for the exhibition—the exhibition will include Act 1—but I am trying to complete a film for the exhibition that introduces the algorithm and is a proof of concept for that algorithm.

JC: You’re answering the question very denotatively, which is fine. But pull it back. Take more distance and consider this. Your process may always have been one of zigzagging. Based upon your screen memory—the formative political primal scene you described—the way you’ve worked as a commercial filmmaker, a curious MFA student, and now as a director of this film is by zigzagging. Even zigzagging between installation and film, between cultural identities, and so forth. Come to think of it, it’s sort of a zigzag-en-abyme. A zigzag hall of mirrors between everything that you’ve done since the beginning, a rabbit hole of zig and zag. And rather than deciding on one direction or another, you find somebody else with whom to zig and zag, and you follow them further down that hole. In fact, between character acting, which is play acting, to live-acting, it’s all really just a repetition of being between various identities. On and on, we go. This madness is your tried and true process!

MMD: I’m going to be a half-century old in just over a year, and the question that I keep asking myself every five years is what am I? Am I a film producer, a film-maker, photographer, a photo-retoucher, researcher or am I a teacher, am I somebody who makes something every five to seven years? I think that it’s just taken me this long to look back at the trajectory in the way that we’re doing right now and say—I guess I’m the zigzagging, the zigzagging is what I am. It’s simply taken me this long to understand that’s an ok way to do things. This piece becomes a performative engagement with zigzagging—because that’s really what it is. Are you making a documentary or are you making a narrative? Well, we’re kind of playing with both, we’re trying to cross the boundary, me and my many brilliant collaborators on this project.

JC: Which is what many are calling “intersectionality.” Most of the time people throw that word out as an academic or political proposition. Accordingly, as either a biopic or as workers’ theater, The Messiah Triangle could have been a standard intersectional, geopolitical, film proposition. But you, as is your way, are making an intersectional film—on every single level, whether it’s your own bio, the material at hand, or your production process which is as professionalized and as Hollywood as it gets—between Hollywood, experimental film and conceptual art. Not to mention a host of geopolitical triangulations at which these aesthetic genres are directed. So these are the things I’m thinking about for the viewer in the room because it’s a problem of suture you’re creating, which is the title of another another influential film, one by David Siegel and Scott McGehee. In their film, as in yours, there’s the problem of suturing onto anyone one thing. I think mobilizing that problematic is powerfully anti-tribal.

MDD: The problem of suture is actually the proposition. And it’s because of our seasoned producer N. Braxton Pope that we could mount a challenge to that problem on such a professional level—not just suture on the register of art, but also on the register of Hollywood filmmaking. We are trying to inhabit both registers, to shuttle back and forth between them. And that has caused some productive confusion with people demanding to know—is this documentary, is this narrative, or is it experimental? Is this a gallery piece, or a film to be shown in a theater. Also, in regard to the content of the piece, this is something that we ran up against many times, people asking—even challenging, “Well are you pro this are you pro that?” I’m pro the problem—I’m pro introducing the problem and leaving you with the problem. It’s not our job to solve the problem, because most often propositions that claim to be solutions are reductive and trite. It is our job to introduce the problem.

JC: Stay on the problem!

MDD: Stay on the problem, yes. Because most people are uncomfortable enough with the problem that they have to run to one side. They have to run to the myth and then they tend to sloganize and say “Well, it’s a land without a people for people without a land!” That becomes a really interesting part of the film which I have to credit my producer, Sarah Szalavitz, with developing: the characters with opposing viewpoints (as you can expect the Israeli Juliano and the Palestinian Juliano would have) will ventriloquize dialogue that was said originally by Anwar Sadat, Ehud Barak, Yasser Arafat, or a number of other historical figures relevant to the region. The characters will recite lines from either side of the argument, without actually giving these historical figures credit—that kind of ventriloquizing became a device as we were revising the script. We considered how much of that we could introduce, how many things can they say that are not their words that would surprise somebody because they came from Arafat or Netanyahu. Our producer Sarah decided to put up quotes in large type on these huge panels that the actors could read, and they could choose to insert them into their dialogue, without telling us or we would script them in if it worked.

So, the problem is this project. How that manifests in a gallery exhibition is going to be very different than how it manifests in a film festival. The entire process has occupied or held both of those positions simultaneously from the beginning.

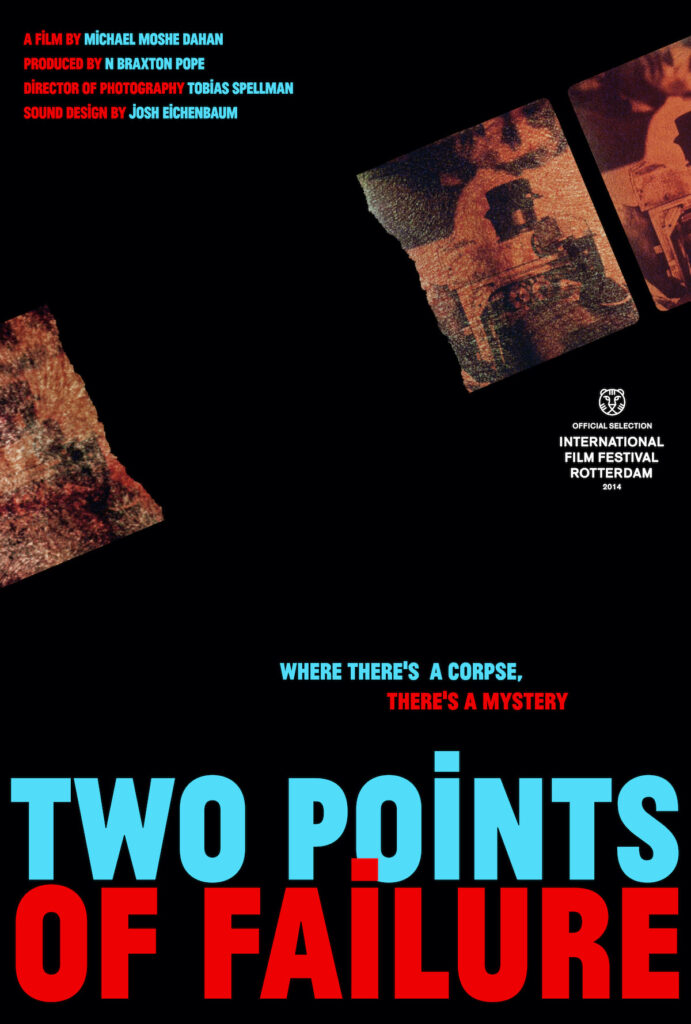

JC: But there’s a myth of reception that encodes both of those spaces. One in film, in which you are in a theater. I’ve been with you in both of these things because this is not the first time you’ve done this, for your second year thesis at UCI you did an art film installation that went to Tribeca Film Festival and Rotterdam Film Festival. I recall that you were as unhappy in the art installation space as you were in the film theater space. You were unhappy in both of those places asking “Why is everybody so limited in this particularly ridiculous way” in the theater, or wondering why even some artists reacted with such resistance to a cinema installation in a gallery.

MDD: Yes, the artists had a problem with it, and were boxed into these spaces with their set of boundaries; it’s not as though the artists were more dextrous thinkers about this.

JC: My point is that both the gallery and the theater are highly mythologized spaces, into which viewers enter with a re-packaged, ideological manner of behavior when given something to look at. Though the ideology attending these spaces may differ, in both cases the spectral operation of suture is at play. To the contrary, there’s a kind of suture-fuck that Yes Repeat No will enact in its art gallery formation, followed by another kind when it goes onto be viewed in film festivals.

MDD: That’s the thing that I’m running up against now in the editing room: I look at these performances, and I see myself getting attached to different paradigms for the right kind of suture. This might be a fantastic take of a scene, but is it the right kind of suture for a gallery? Is it a different take that goes in each one, or is it a different structure? I’m really interested in seeing how those two things play out because I don’t know—it’s a process with no predetermined outcome.

JC: That’s why you’ve generally taken on a deconstructive approach—to my happiness because it’s just what I’m interested in—rather than an oppositional or an identitarian one, with regards to suture. You don’t oppose a dominant form of suture (or identification) with an equally conventional, though marginalized one. Rather, you tweak it, just enough to make the whole operation transparent, but not disabled. This way, people see themselves looking at the Other but not having returned back what they’d expect, all the while having enough returned that they maintain an interest, analogously, in being this kid who’s happily zigzagging along the road. The kid who says I have to do it right, but I don’t know how to do it, so I’ll just keep doing it. A kind of do wrong until you get it right kind of ethos…

MDD: And the more right you try to be, the more wrong you’re getting and the more confused. When that experience—walking home and crossing the road too many times—came up and I started to make work about it I thought it was just something I remembered from my childhood. Yet it becomes a metaphor for what I’ve become and the operation I’ve performed my entire life. I work in the film business, and then I go back to school to be a photographer, but then I’m not a photographer, but then I want to be an artist, but then I’m not an artist, but then I want to go to do research…

JC:…Since I have to write my dissertation, I think I’ll go make a film…

MDD: Exactly, so really what I was doing was just arriving at the place that I could have chosen from the beginning and make films. Yet to have begun with that is not the same as to have arrived through the process of zigzag, or to have arrived at the process of zigzag.

JC: But you know what they call that in other worlds: Adorno’s negative dialectics. It works on a spiral motif, as opposed to the normative dialectics, which would work this way: I’m done making the film, now I’ll do the PhD, and next week maybe I’ll grind lenses. Negative dialectics proceeds exactly as you have.

MDD: Ultimately I think it’s just taken me this long to own that this is the way I do things.

JC: This is funny because I didn’t know until this conversation what the reference for the film’s title was. You never told me that the “yes repeat no” was a military phrase. That’s really interesting because “yes repeat no” is the performative spiraling of negative dialectics, it is the deconstructive version of the binary “yes” and “no.”